How is your life in South Africa?

I am originally from Germany, and living in South Africa has been an adventure. I moved to South Africa just before the COVID-19 pandemic started. I was finishing my training and then I had to move back to Germany and go through quarantine and lockdown. Finally, I’ve managed to move back to South Africa and I expect to be here at least for two years.

Africa, in general, and South Africa, in particular, never lets you stop and take a break — here I experience a vibrant life. Especially when you live in the bush, every day there is something happening that you did not expect, so the bush will never let you settle down. Long story short, my journey to South Africa has been the greatest journey of my life.

Could you briefly explain to us what your work here consists of?

I am a safari guide and I also work as a field/trails guide at Kings Camp Lodge in South Africa. Usually I get up at 4 am and start working. I am also a nature-conservation student; I study it part-time. When everybody else is sleeping, I’m normally studying or taking care of my social-media profiles. I keep myself busy with communication and walking safaris and I like to see myself as an educator. I like to teach people about the importance of nature and biodiversity. This is my grain of sand to conservation.

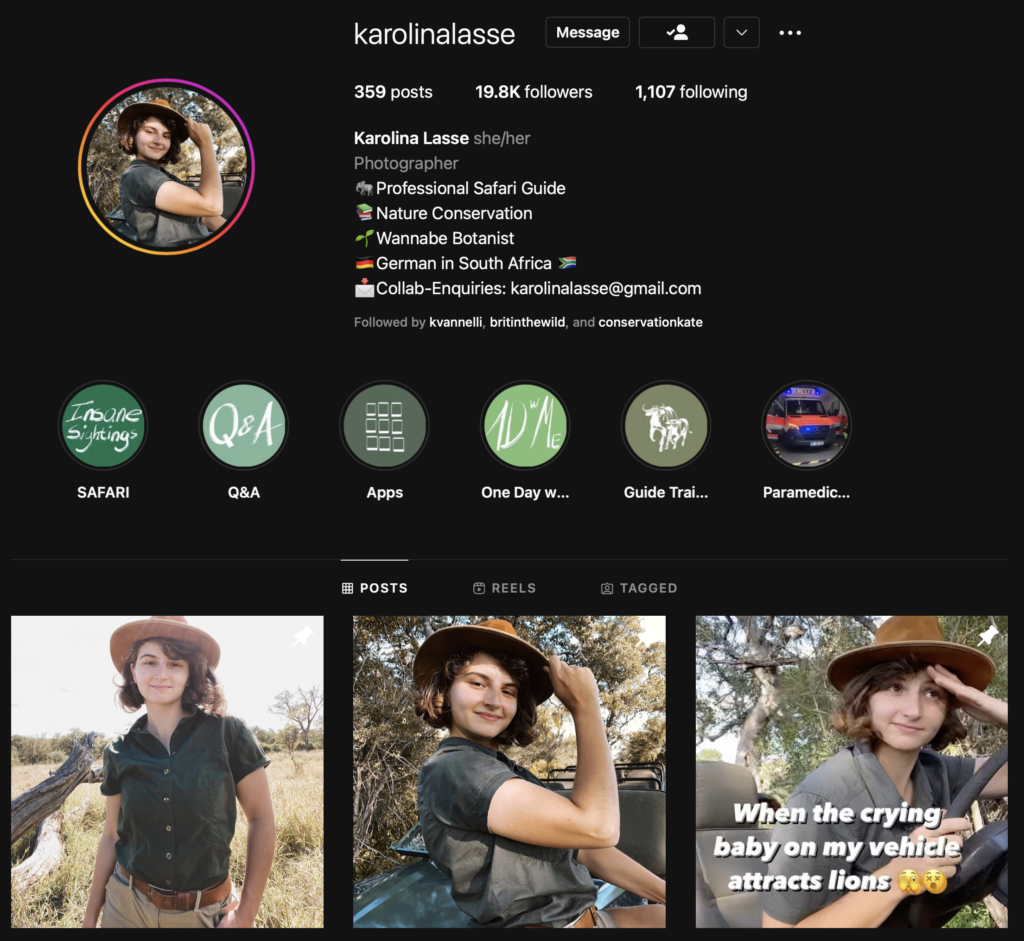

With almost 20K followers, you are a very popular figure on Instagram. What are you trying to communicate?

I didn’t feel like the safari industry was represented enough on social media, so I wanted to explain how our life is and what we really do. When you are a guide, you have so much material and so many stories, both from your daily work as well as from your guests. It is mind-blowing to see how people perceive nature depending on where they come from. Europeans have a very different sense of what nature is compared to North Americans or Russians.

Also, as a safari guide, you go through many unbelievable situations every day, so I wanted to use social media to explain that. And very slowly, but regularly, I’ve started to get feedback. At the beginning, I struggled to understand what was the message I wanted to communicate. But then everything started to move smoothly. I think as an influencer, I’m holding a big responsibility because somehow I’m impacting… the way many people in the world will perceive us.

Where do your followers come from?

In the beginning, 99 percent of them were from South Africa, so they were very aware of what was I talking about, like the way you should behave with animals, how to avoid certain dangers… but now I have many followers from other countries, so I’ve started to change my point of view and the way I explain my stories. Now I try to explain them from the animal’s point of view.

What is the question you get asked the most?

I think it is, “should I feed animals when I’m touring in a national park?” Obviously you shouldn’t; wild animals should not rely on humans for survival. I think teaching that to people is one of the most important things one can do.

You always raise serious questions with great originality. What kind of feedback do you usually get?

Ninety percent of the messages I’m getting are positive. People encourage me with my work and find my content useful, as they find it funny and light, and they say they understand better what we do.

Also, the safari-guiding job is pretty much dominated by men, so people are surprised to find a woman doing that job. So I get asked about that a lot too.

How do you see the state of South Africa in terms of nature conservation?

It is a very difficult question, because nature conservation involves many different things. It is not simply protecting nature and animals, it goes hand in hand with social structure, infrastructure, and with the government. I do work next to Kruger National Park and I see many people engaged with nature conservation. Their commitment and their passion is mind-blowing; they truly give their lives to protect animals.

Especially the rhinos, due to illegal hunting and trafficking, we lose about two rhinos every day. However, lots of funds are coming from South Africa and other countries, and, although sometimes it might look like a hopeless fight, we can’t stop fighting.

What policies should be improved in this respect?

There are many animals who are in danger which are not as popular as rhinos, for example. Birds have a critical impact on biodiversity and they are being overlooked, I think simply because they are not as majestic as the rhino. South African vultures play a key role in balancing the ecosystem and they are at risk, but a rhino would get more funds because it is cuter (for humans) than a scary vulture.

This might sound a bit controversial, but we receive lots of funding for nature conservation, and sometimes these funds are coming from unexpected sources. For instance, the hunting industry invests in nature conservation, or there are efforts put on the communities living within national parks. Sometimes conservation is not as cute as you would think. Burning the bush is a very important part of nature conservation, but it doesn’t look good in the pictures.

Is there a strong sector of non-governmental organizations carrying on effective initiatives?

I don’t know how many there are, but people have put a lot of effort here and it is impressive to see how many ongoing nature-conservation initiatives are currently taking place. People on the ground, people in the field, are truly doing an amazing job.

In the time you have been working, what made you feel most impotent?

Sometimes people humanize animals and would do to them what we would do to a human in order to save them. That makes me feel uncomfortable, because that’s not how nature conservation works. What helps animals long term might not be easy to accept in the short term.

For instance, in Africa, we had many campaigns to protect elephants; everywhere you could see messages like “save the elephants.” But these campaigns did not take into account the people who live close to the elephants, so, as the elephant numbers increased, some communities developed an interest in getting rid of them because they might be eating their fruits or creating an imbalance in their system. So, in a sense, this campaign kind of increased the risk to the elephants of being killed. It would have been better to invest in finding a balance between humans and wildlife, and that is also part of what a nature conservationist would do.

Have you seen an improvement in the quality and biodiversity of the places and species you work with?

For decades, people have been told about climate change and [its] consequences, and we are already feeling its effects. We see that biodiversity is going down day by day, people know what’s going on, but maybe people have been scared to endlessly and they’ve been blamed too much. What can you do when you’ve been responsible for so much damage and when there’s really no hope left?

I think organizations such as This is My Earth play a very important role in giving people hope and the sense that they are participating in conservation. It is about feeling you are doing something and taking action.

A big challenge for you is…

I think a big challenge for me is when I have people coming over that have never been to real wild environments. They come with so many Disney-movie ideas about how animals should look like or how they interact. They charge animals with their emotions, but this is not how animals work. Like the lion is the king of the jungle, yes, but lions are also stealing lots of food from other animals!

What do you think of democratic, transparent and scientific conservation projects like those of This is My Earth?

This is My Earth is truly participating in the process of protecting nature and using science to save as much biodiversity as possible. Not giving up and not losing hope are the most important things, and TiME brings that to everyone.

If you feel like you want to help and you want to participate, TiME is a good starting place to do so.

What advice would you give to someone who wanted to follow in your footsteps?

I would say, “find what you are good at and, at the moment you start participating and taking action, everything will make more sense to you. Keep on going and you will succeed!”

If we are speaking about safari-guide work, I would suggest to them to choose a place they like and also find a working and lifestyle philosophy they feel comfortable with, because there are many places where you can live and all of them are very different. In my case, we are like a big family here and we share all sorts of maintenance tasks. That works for me, but I would tell you to make sure you are engaging in the type of work you really want.

TiME is truly participating in the process of protecting nature. If you feel like you want to help, This is My Earth is a good starting place to do so

Regarding new generations, what message would you send to them?

Our Earth is going a big global change. Mindsets are being changed, balance has broken down, and a big part of it is because social media is playing a key role in shaping new perspectives and public debates. We were not aware of some of the problems around the world, and now we have access to what’s going on.

I would encourage new generations to keep on believing and trusting in the process. I would tell them to engage and follow what is really going on. I can tell you, here in South Africa, young people are getting involved, and they have almost nothing they can call “their own,” and yet they are giving everything they have. People die in the name of nature conservation in my immediate surroundings. If this is not reason enough to keep going, I don’t know what it is.

Every day I will try to protect this beautiful world, because I’m privileged to be able to enjoy it. I know many people that would do the same. I’m not the only one that is thinking like that, and neither are you.