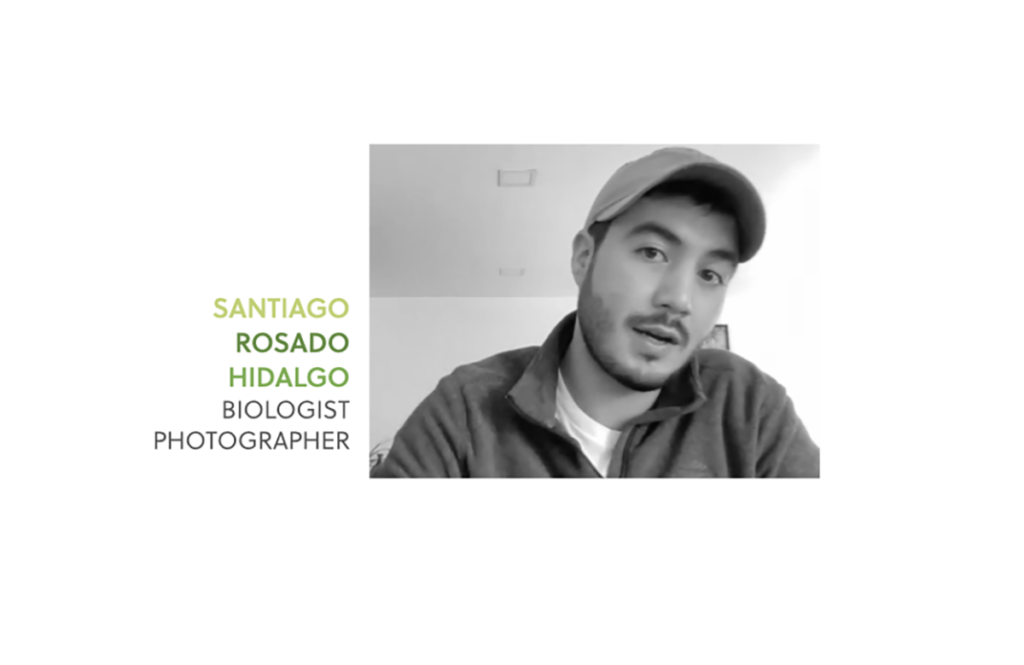

[READ THE ORIGINAL INTERVIEW IN SPANISH] – We interviewed Santiago Rosado Hidalgo, a biologist and photographer at the El Silencio reserve in Colombia, and a contributor to This is My Earth. He thinks that conservation always needs support; we never have a spare hand.

Hi Santiago, how would you introduce yourself?

Good morning, my name is Santiago Rosado Hidalgo. I am a Colombian biologist and I have been dedicated for years to nature-conservation strategies in our country, linked to a very nice project that is part of the Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, in that we preserve and monitor the El Silencio Nature Reserve, which is an exciting area in the Colombian Middle-Magdalena, a region with an overwhelming history of violence and deforestation, which has nevertheless been flourishing and resisting. What we do now is to preserve and watch over everything in the reserve.

Do you work alone at El Silencio?

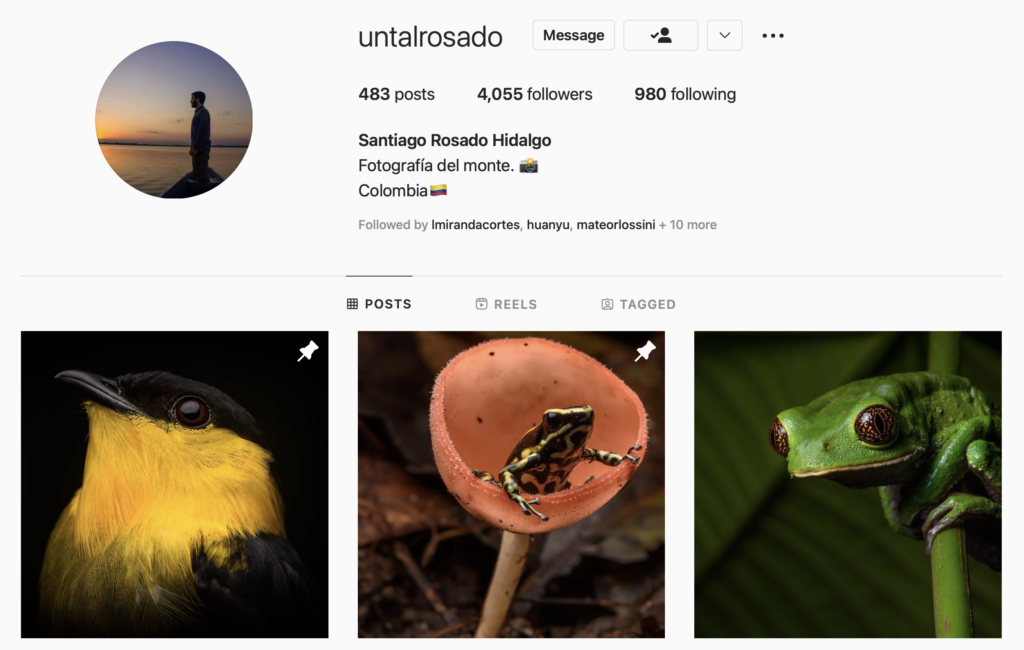

Yes. Over the years, I have also developed a great interest in photography that has grown. I spend part of my time traveling, taking photos, and expanding my catalog of animals.

What can you tell us about the tragic story behind El Silencio?

It is not so much El Silencio as such but in the entire region surrounding it. This reserve is in the Magdalena Valley and historically has been a plain between two mountain ranges. An armed conflict developed, and there was a struggle for the territory’s resources. Armed groups began to exercise governance over some of these territories. The control of the Magdalena river, the largest in Colombia, has always been linked to violent struggle, trade, and many tensions because this river has been the economic artery of all these places, not only the legal economy but also the illegal.

This set of conditions in a large territory with a lack of governance from the central government, together with the interests of the population (above all cattle ranchers), began to combine into a cocktail that brought more violence and endangered the forests, by approving a law for the privatization of land for cattle ranching.

After the peace process, now we feel new air and have seen a change. My organization, associated with This is My Earth, has been doing incredible work in the region — educational and training work that is bearing fruit.

Which of these “fruit” would you highlight?

Undoubtedly, the acquisition of El Silencio with the help of organizations that saw its biodiversity was a great achievement for everyone. We started with about 10 hectares and now we cover almost 10,000. The most important thing is its value. El Silencio is still standing almost fully intact and its ecological conditions and its biological richness are unique and are still in optimal condition.

How is your work helping to change the history of the region?

It is helping a lot to bring it back to what it really is, a place of supreme beauty filled with pulsating biodiversity. Conservation always needs support; we never have a spare hand.

Broadly speaking, what objectives do you have in the region?

We have several working groups with people linked to various fields, from the most social side to conservation for the most natural part. In general, our objective is to generate well-being in the forest, the ecosystems, the animals, and the people who inhabit the region, and to do so in a sustainable and permanent way over time. This place is life, and it is a place that can guarantee the quality of life of many people.

According to you, what example illustrates these efforts?

For example, the swamps are essential, because that is where most of the fishing resources [can be found, where] the fish that live in the river reproduce. They are nurseries for millions of fish that sometime later will become an economic and nutritional resource for many communities. Of course, you have to exploit them in a proportionate and sustainable way, and that is what we try to do with educational and conservation actions.

Does your documentary “BETWEEN FISH AND TROJAS: For Our Food Sovereignty” go in this direction?

This was an incredible job that Catalina Giraldo did, which was part of a project carried out with the Fundación Biodiversa and the Ministry of Science. What we did there was train the communities and people close to them on sustainable agriculture, food sovereignty, and suitable and ecological agricultural infrastructure. It was a fantastic job. It sums up our work with the community very well.

What is food sovereignty for you?

For me, food sovereignty is that everyone can eat when they want to eat. How can we achieve it? In these places and in these remote regions of the country, many people are dependent on what they can produce daily, which is why this issue is very complicated in these communities. What we want is for everyone to be able to grow and harvest their food, meaning that, at any time, I can have what I produce and sell or share what I have leftover.

As a photographer, what does a photograph have to have to be beautiful and expressive?

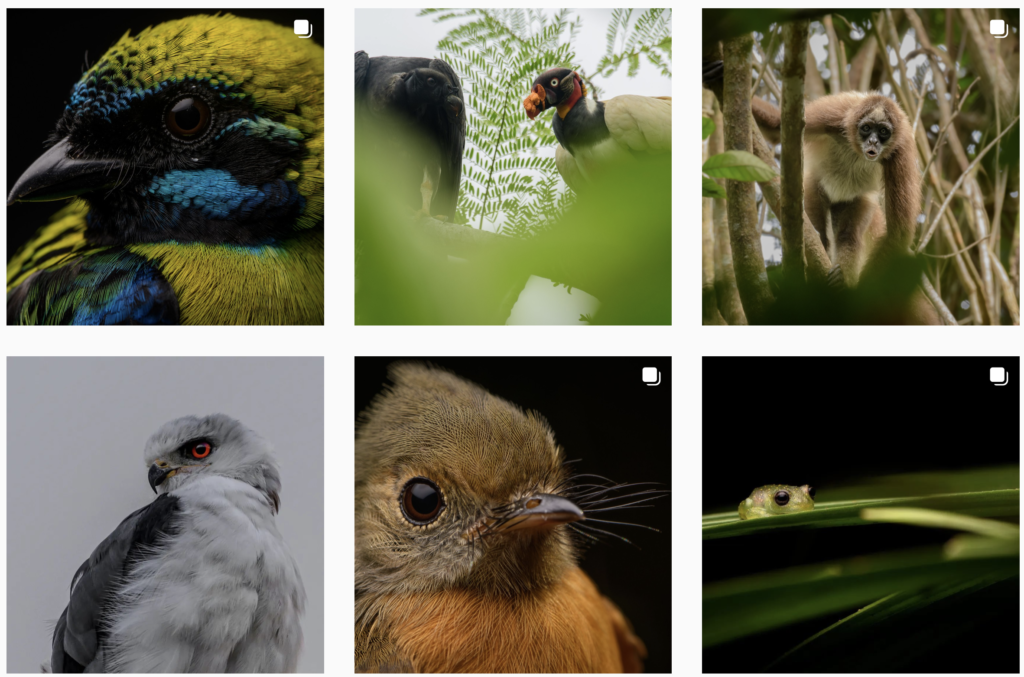

That’s a very cool question! Through photos, we can generate some empathy, although not everyone likes the same thing. Let’s say that it is not the same to develop empathy for a frog as for a bird. Ultimately, it is about telling a story. During this time working as a photographer, you realize that if you only look at the animal, you are overlooking natural history, the place where it is. Everything that makes up this animal, its environment, its history, that generates a story that people can understand.

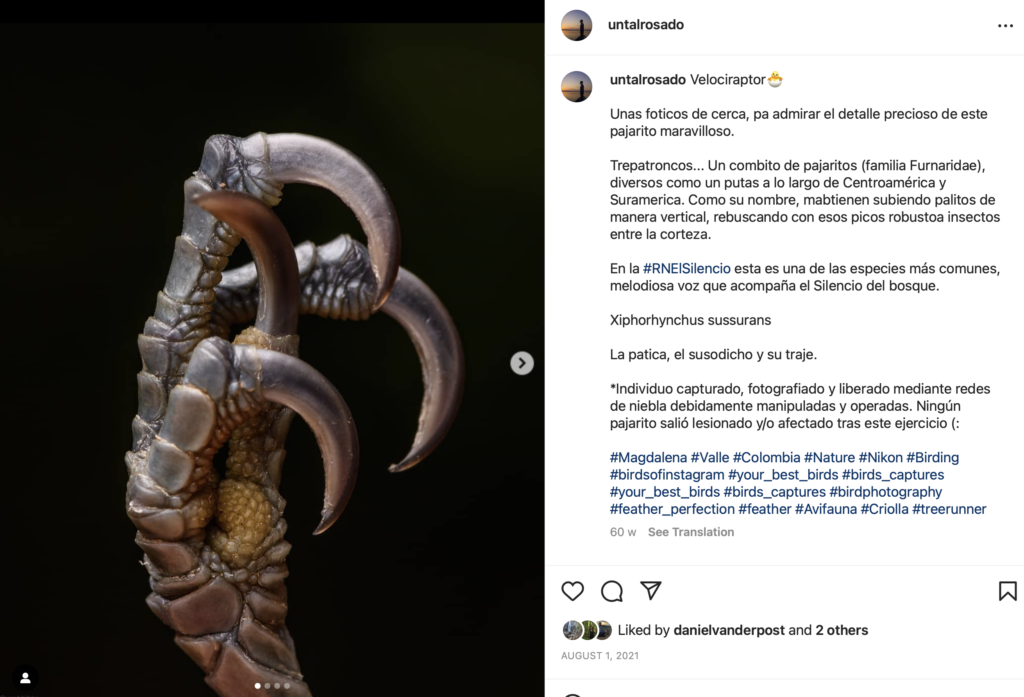

When I started trying techniques with “macro-photography,” I began to realize that I could capture very interesting realities. A hilarious story happened to me: we went to the reserve. We did our usual exercises with the rangers [and] with the ornithologists. We saw how these bird specialists work, how they measure the [birds], etc. While I was taking photos of this whole process, I began to zoom in.

I was showing the legs of a bird that was in the hand of one of the ornithologists. When I showed people the pictures of the bird, no one saw the feathers or the spectacular colors that the bird had in its eyes; everyone noticed the legs. Everyone was impressed because the bird’s foot totally resembled that of a dinosaur. It was unbelievable, I hadn’t even realized it. It is very important to look at these details, to understand the entire biological load behind each living being. I will always remember this paw.

It all started with this leg…

It was pretty crazy because this group of birds evolved to walk on logs vertically. Its legs have a reinforced rear finger, that is to say that it is much thicker with long and wide nails. All these types of adaptations have a lot to do with the natural history of the animal and its environment. In the long run, analyzing these details is very helpful to the research community because these data on natural history, behavior, and ecology are very valid. In that sense, my photos can help.

What is a day in your life like as a photographer?

I go to the El Silencio reserve about 15 days a month. It is a place that I know and where I move well. I like getting lost in the jungles and knowing that I’m going to find myself. But what’s really cool and never ceases to amaze is that there is never a day like it; you never know what you’re going to find. No matter how much you go, no matter how much you walk, and no matter how much you recognize the nature that surrounds the place, the experience is never the same.

Can you explain to us the process of taking a photograph?

The first thing I want to say is that I am not like some of my friends who go to the place where they want to take pictures and spend four days there until they find the perfect moment with the tripod and the [lens] hood. I’m more for going for a walk and seeing what happens. [I am] obviously always waiting for the perfect photograph — and here luck plays an important role — but what I like the most is the part of walking through the forest, listening to the sounds, and connecting with nature.

At El Silencio, I have the pleasure of sharing my time with Pedro and Julio and with our rangers. Each one of us has built a part of the knowledge of this place, and when we all go out together, we get very involved. This is important because the jungle is essentially a dynamic place, and you need help to move well in it.

What do you mean, it’s “a dynamic place”?

In the jungle, a lot is going on all the time; nothing is the same at the end of the day. I would even tell you that there are changes every few minutes, not only the landscape, but also at a micro level: the leaves, the fungi, the frogs associated with the fungi of each season, fruit that only come out in the dry season, the associations of plants with different animals in the environment… Every time, they call more attention to biological associations between species. I try to focus on that.

What is the greatest challenge of explaining these biological associations through photography?

Many times a close-up photo of a monkey eating a flower is something that you already know will be successful, that people can understand and relate to. But I think you have to look a little outside the box and try to narrate the natural stories, because in the end, it is much more enriching for the audience.

What are the references in the world of photography that have helped you become the photographer you are now?

There are many, but there is a Colombian colleague, Frey Gómez, who was in El Silencio, and in six days, I had a photography master class. He has an incredible eye, an ecological sensibility, and a vision that inspires you. I think we agree on this idea of showing natural history, of showing what is behind the animal and not just the animal. I think he changed my way of thinking. In Colombia, there is a big photography movement, and I think it is important to give your work a personal touch, give it your style. And, above all, [I want to give] a lot of respect to all the professionals dedicated to photographing nature, because it is a very hard world.

Living in a capital like Bogotá, is it easy for you to find natural spaces?

Nearby, we have the Chingaza National Park, where it is easy to find Andean bears, and [it is] a wonderful place. The city’s water comes from this incredible wasteland, [and] there are also forests on its flanks. We often go to Chingaza, and I have been putting this storytelling of the territory and its inhabitants into practice. My speech is: “Look, Colombians, this wonderful place next to Bogotá is incredible, and this is the value it has for the country’s ecosystem.”

You must try to go beyond the animal and look further. In a close-up, we can talk about many things: the skin of a poison dart frog, the reproduction strategies of a lizard by looking at the scales on its neck, or the interactions between pollinators and plants.

What species have cost you the most to photograph?

I think a curassow, one of the conservation targets of the reserve. It is an animal very similar to a turkey, black in color and very large. It is a bird closely associated with forests in a good state of conservation. In addition, it is an endemic bird; it is only found in certain parts of Colombia, and sadly, its habitat and population have been greatly reduced. In El Silencio, luckily, we have been seeing more curassows in recent years. It is a supremely agile and elusive animal: I have seen it once but I have not had time to take out the camera. The curassow is still a thorn in my side..

In Colombia, there are always exciting animals, even legendary ones. For me, there are four almost mythical species; they are the Magdalena Spider Monkeys, with which I have had very close encounters; the curassow, which I have been able to see on a few occasions; and finally, the jaguar and tapir, which I have never seen. The jaguar is a dream; I hope to meet him one day. And the tapir is a scarce animal and is extremely threatened. In El Silencio, we know that they are there, because we have seen footprints, but we have never seen them.

When do you think your mission in El Silencio will end?

I believe that the conservation mission in the tropics never ends. It is a long-term process, and the idea is that each one of us who is here will never disconnect: after walking so many kilometers inside the forest, after the heat, after the sacrifice, you create an intimate bond with the forest, something unique. I plan to continue to see the El Silencio reserve grow, because it is growing.

What can you say about Colombian policies regarding nature conservation?

Right now, there is a lot of uncertainty, but in Colombia, the scientific community is substantial. I believe that there are many talented researchers and scientists with ideas to carry out effective conservation strategies, and to do so using the communities’ own knowledge. Without the community, nothing can be done. With everything that has happened with the conflict in Colombia, people have realized the importance of conserving. A fairly strong movement has begun to take shape in relation to nature conservation.

It is necessary to work hand in hand with the local community, the scientific community, and state entities to articulate strategies that attack the root problem. Administrations, governments, biologists and volunteers won’t carry out these processes in three or four years because the conservation processes can take decades. First, you have to go in and gain the trust of the local communities, try to connect with them, and turn them into allies… but I am optimistic.

What do you think of the This is My Earth project?

I think it’s fantastic that TiME and other organizations commit to supporting conservation projects. Here in the tropics, it is tough for us to find sources of financing and support. These years working at El Silencio, I have realized the importance of having an ally, someone who thinks like you. TiME stepped into El Silencio and helped us secure a forest that was very disconnected from the rest of the ecosystem, and thankfully is now connected to the rest, allowing species to flourish and expand. Every bit of land is key, and having the support of people like TiME volunteers is crucial.

What would you say to someone to get them to participate in TiME?

Let them do it without thinking. If you are motivated by the environment and nature conservation, if you want to change things, participate in This is My Earth. Conservation always needs support; we never have a spare hand.

This is My Earth entered El Silencio and helped us secure a forest that was very disconnected from the rest of the ecosystem.

Photography started for you as a hobby to try to explain biology. Have you learned things you didn’t know about biology thanks to photography?

Yes, a lot of things. For example, patience is a skill that I am developing. Reaching points of extreme fatigue, when you are dirty, muddy, in the middle of the humidity, when your mind is telling you to wait a little longer, photography teaches you to be resilient and wait — and it is very addictive. It also trains you and informs you about rare species that you want to photograph. Photography has taught me to see things more broadly and to open my mind and eyes.

Thank you very much for your TiME!