Sequestering carbon is one of the main strategies for capping the global temperature rise at less than 1.5° Celsius (2.7° Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. Because this is an urgent strategy, many studies are finding the more sustainable ways to achieve the global. goal. And it turns out that indigenous people are better at protecting the Amazon’s last carbon sinks.

Experts warn that Amazon is on the verge of “tipping over” from being a net sink to a net source. This would unleash dramatic consequences, making the global temperature goal much more challenging, if not impossible.

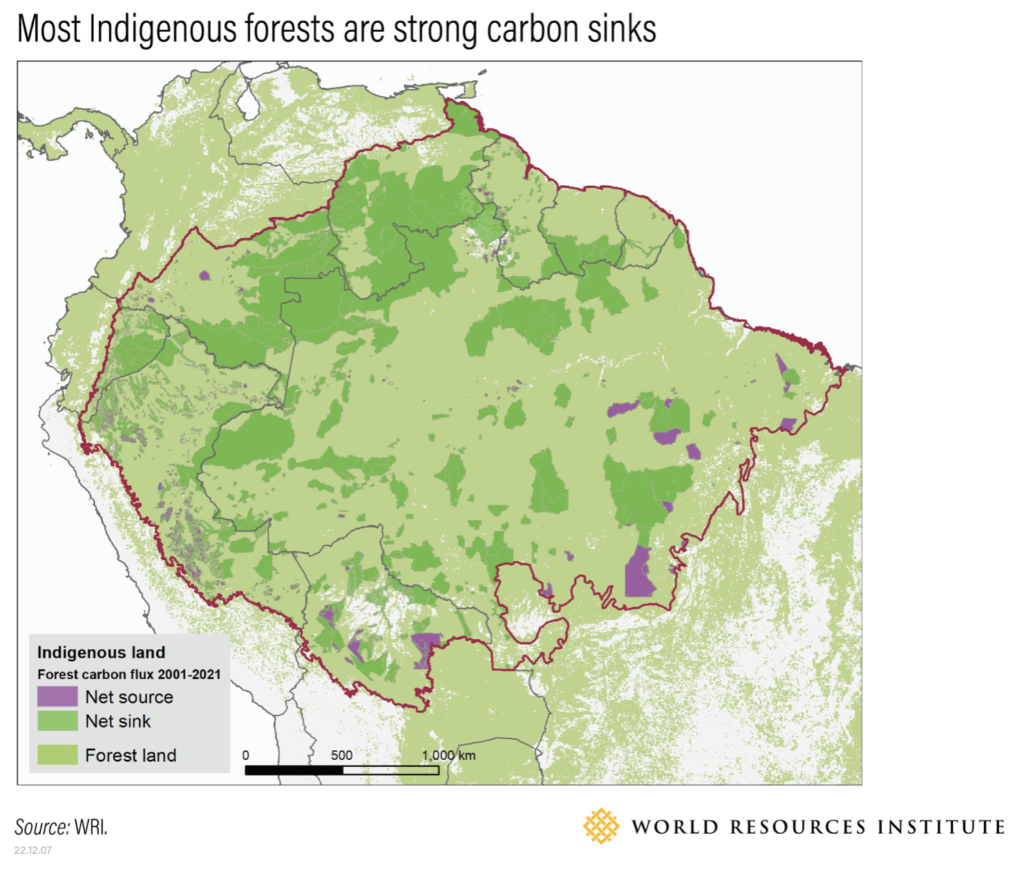

When asked who can best manage the forests, the answer is not long in coming. The evidence is crystal clear. In areas of the Amazon managed by Indigenous communities. Therefore, Indigenous people are better at protecting the Amazon’s last carbon sinks.

The importance of carbon sinks

Woods tend to be carbon sinks rather than carbon sources. In contrast, areas under different management tend to have already passed their tipping point.

A new study shows that some of the last remaining carbon sinks in the Amazon Rainforest are managed mainly by Indigenous people. The World Resources Institute has published the report, underscoring the need to help Indigenous people and other local communities safeguard their forest homes and preserve some of the Amazon’s remaining carbon sinks.

“As more forests are lost and converted to other uses, Indigenous and other community forests stand out as stable carbon sinks that must be secured,” says co-author Peter Veit, director of WRI’s Land and Resource Rights Initiative, and adds, “Should community forests be degraded or lost, large stocks of carbon would be released into the atmosphere, and the lands would no longer be able to sequester the same amount of carbon.”

Indigenous people are good carbon sinks managers

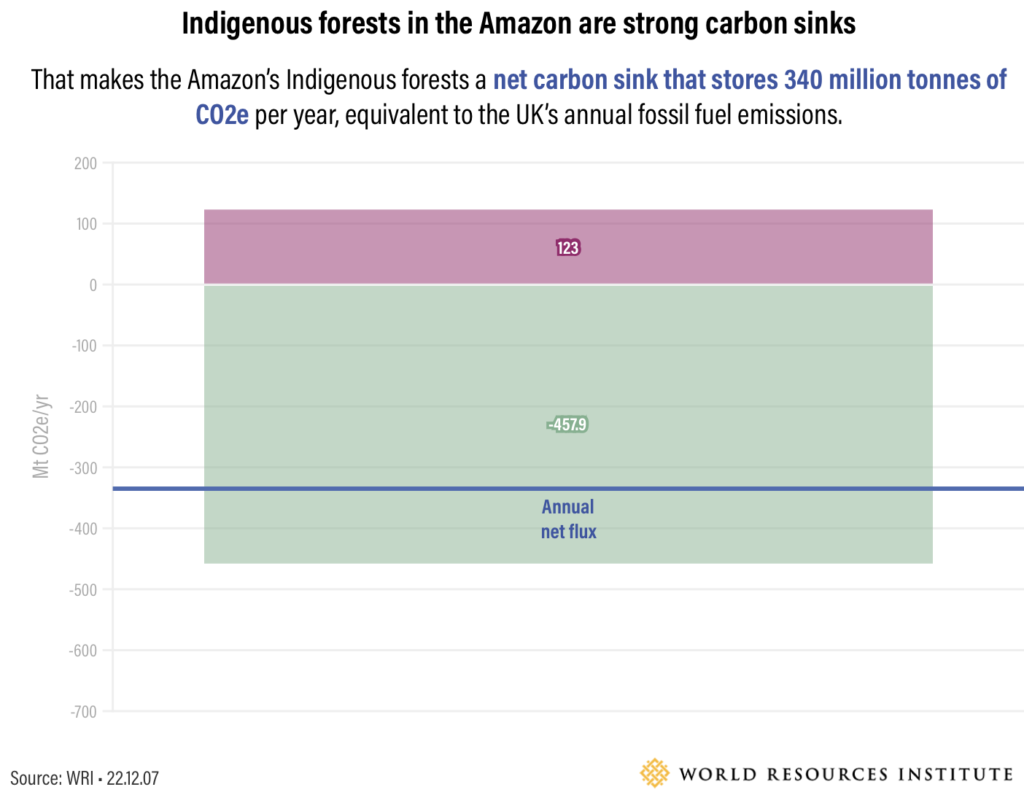

Areas of the Amazon managed by Indigenous people have sequestered more carbon than they’ve emitted. Between 2001 and 2021, they emitted around 120 million tons of CO2 annually while removing 460 million tons, a net total of 340 million metric tons removed. That’s equivalent to the U.K.’s annual fossil fuel emissions.

Meanwhile, areas under different kinds of management have tended to be net carbon sources.

Forests in the Amazon bioregion outside Indigenous lands were collectively a net carbon source between 2001 and 2021. These forests emitted 1.3 billion tonnes of CO2e/year due to forest loss. They removed about 1 billion tonnes of CO2/year, making them a net source of approximately 270 million tonnes of CO2e/year, equivalent to the annual fossil fuel emissions from France.

Indigenous Forests Produce Far Fewer Emissions than Other Forests

While Amazonian countries with more Indigenous forest area naturally had more significant carbon fluxes, the annual carbon flux per hectare — or the carbon flux density — varied little among the countries’ relatively stable, mature Indigenous forests. From 2001 to 2021, the carbon flux density ranged from a net sink of roughly 0.78 tonnes CO2e/hectare/year in the Bolivian Amazon to 2.0 tonnes CO2e/hectare/year in the Colombian Amazon.

Outside Indigenous lands, however, annual net carbon flux density varied considerably, from forests in the Brazilian Amazon emitting 1.4 tonnes CO2e/hectare/year to forests in French Guyana removing 2.0 tonnes CO2e/hectare/year. This reflects the differences across Amazonian countries in how much forest outside Indigenous lands is degraded and lost.

As journalist Marwell Radwin points out, “Bilateral, multilateral, and private foundations donated about $2.7 billion to community forest management efforts in tropical countries between 2011 and 2020, representing less than 1% of official development assistance donations to climate change mitigation”.

In fact, at the COP26 climate change conference in 2021, funders pledged $1.7 billion to Indigenous and community forest conservation efforts. But only 7% went directly to the organizations led by Indigenous groups, according to a progress report issued during last year’s COP27 summit.

The WRI report also urges increased government support for Indigenous land management and, in its conclusions, this study proposes that the new strategies are based upon three fundamental pillars:

- Recognize community lands in climate strategies: Forested countries with large areas of community land should make them a central component of their climate action strategies. For example, in Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico, Indigenous forests sequester emissions equivalent to an average of 30% of their countries’ national emissions-reduction pledges, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

- Secure and protect community lands: Governments should establish accessible and transparent procedures to register community land in a government cadaster and document it with a land certificate or title. Securing community lands is a low-cost, high-benefit investment and a cost-effective carbon mitigation measure compared to other carbon capture and storage approaches.

- Increase funding to communities. Governments and donors should channel more financial resources to communities and their organizations, recognizing that they’re some of the world’s best forest protectors. From 2011 to 2020, bilateral, multilateral, and private foundation donors disbursed about $2.7 billion for projects supporting community forest management in tropical countries, less than 1% of ODA for climate change and less than 5% of ODA for general environmental protection.

“There is much that can be done to protect forests and the communities who call them home,” the report says. “At stake is not just the fate of carbon, but people’s lives and lifestyles.”

This is My Earth and the Amazon

As you may already know, This is My Earth has long been working with indigenous communities and local NGOs to return biodiversity-rich land to its owners.

This study undoubtedly reinforces our belief that our model not only directly impacts the empowerment of thousands of volunteers worldwide but also benefits the health and well-being of forests and the communities that support them.

At TiME we have launched several participatory processes in the Amazon, such as the purchase of the Sun Angel’s Garden in Peru, thanks to which we created a chain of double protection over one of the key reserves in the entire region. Your micro-donations protected the beautiful gardens by creating a U-shaped area and then signed it over to the local conservation organization, the Asociación de Productores Agropecuarios La Primavera (APALP).