This is My Earth had the privilege of speaking with Constantino Aucca Chutas, recipient of the UN Champions of the Earth award. He thinks “there should be more projects like TiME”. His work across six countries in South America, through the organizations he presides over, Acción Andina and the Andean Ecosystems (ECOAN), is internationally respected and recognized.

How would you like to present yourself?

My name is Constantino Chutas. I am the president of the Andean Ecosystems Association and the president of Andean Action, two national and international initiatives for restoring habitats along the high Andes.

Do you remember a moment in your youth or when you were a child when you realized that nature was in danger?

Having spent my childhood walking my grandparents’ cows and sheep, in contact with the river and the forest, and enjoying the beauty of the Andean landscapes, [that] was enough to grow up loving nature. Before protecting, you must love.

Would you like to see more passion in the world of nature conservation?

Yes. I ask all leaders to develop passion and love for what they do so that they are truly satisfied. The satisfaction of protecting nature cannot be paid for with all the salary in the world.

Without love and passion, you can’t achieve anything.

You can’t; you have to get emotionally involved. When I started my conservation work, I found all these local communities full of hope for the people we would talk to and love for their lands.

What do you remember from this period?

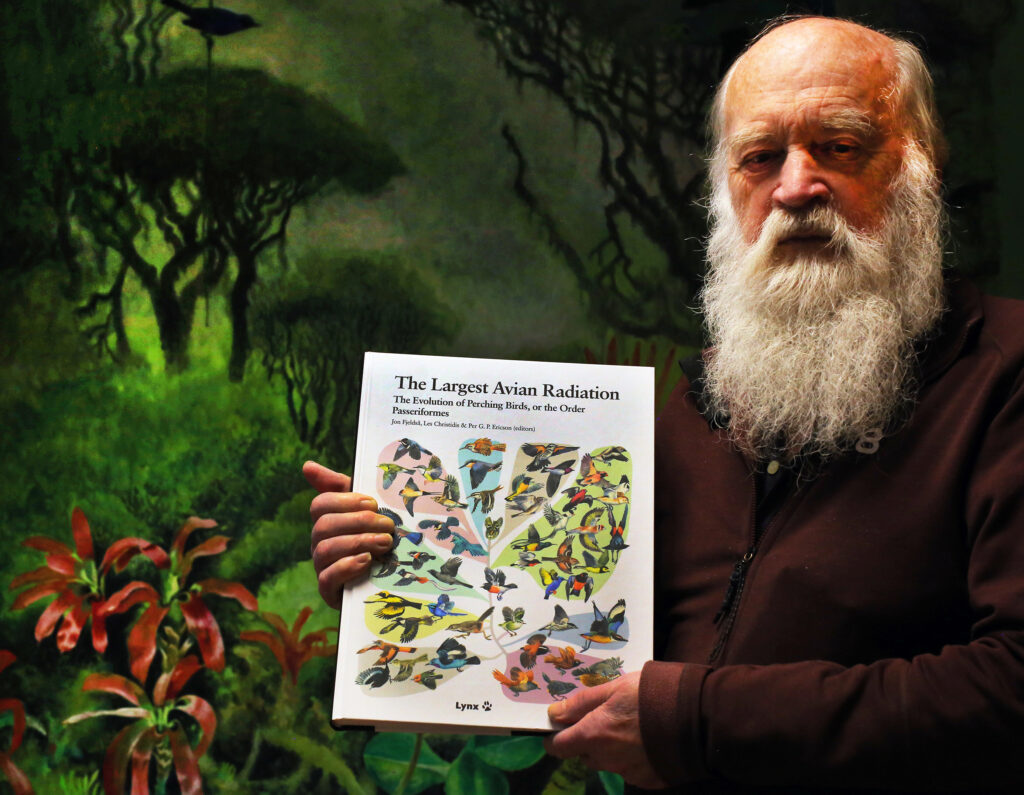

I remember many meetings with one of my mentors, Jon Fjeldså, perhaps the most famous ornithologist in the world. With him, I crossed the mountains of Apurímac and Ayacucho, in the middle of the emergency zone due to terrorism.

We had several encounters with terrorists, and when they asked us what we were doing there, we told them that we were studying the forests and the birds. The terrorists themselves told us, “You are crazy. Do you know that you can die for that?”

How did you react?

We told them that what we did was important and could generate income for them and their communities. We explained to them that several Critically Endangered species existed in the area.

We photographed the animals and showed them to them to make them understand the situation.

Then my mentor told me, “I’m going to give you the doctorate, but I ask you to please stay here studying and taking care of these forests that no one takes care of, because they need you. In the future, people will pay you to teach about its importance.”

How did you take it?

When one of the most famous ornithologists in the world tells you this, you have to consider it. But, of course, what do you eat?

Now, I take stock of life and am happy to have taken this responsibility because this is a historic moment. I have survived terrorism and have been left alive in the most beautiful place in the world; life fills you.

How has your connection with native communities worked?

We work from several axes. We help communities understand that planting trees is a solution for the better management of their resources, also natural. Now journalists go to ask these communities, “why do you plant trees?” And they answer, “for the water.”

Water is life, economy, and future for the children of the Andes. These Andean communities understand that the climate is changing, because water is scarce.

Is it a feeling shared by everyone?

When you start talking to the old people there, in the passes of the Andes, while they are chewing coca, they tell you, “Look at that mountain; it’s called Salkantay, which means the mountain of the devil. And 30 years ago it had snow; now it doesn’t. Could we be doing something wrong, and Mother Earth is punishing us?”

What a lesson in humility…

True. No PhD could understand that. Many people live in misery and feel guilty about climate change to which only a small minority of humanity contributes.

Can you imagine if the people who pollute had that same position?

It is very shocking. A miserable person at the top of a hill thinks he is harming the environment and asks for more trees to be planted.

How does nature conservation help boost the economy of these people?

We rescue the culture of these people, which is forgotten. We have planted ten million trees in five countries. It may help contain climate change, prevent deglaciation in the Andes, and keep water flowing and feeding the valleys.

And this water can reach cities — and we must teach children that it does not come from a plastic bottle!

Conservation is not a letterhead nor a book; it is something that, if you do not do and take action, you do not understand. The rest are words. Conservation without money is a conversation.

What do you think of the conversations that are had at summits, like COP?

Each meeting costs $90 million, and we have yet to achieve anything substantial so far. Some of the participants in these summits have already been to 20 meetings before, and the first thing they ask is, “Where will the next one be?” This is paid tourism in the name of nature conservation; this is hypocrisy.

How should we do it?

I thank all the big countries that donate money to people experiencing poverty. For example, the Nordic countries send millions to South America. But you have to get involved in the management of these funds. When you are donating to clean your conscience, you will ignore the results.

And in Peru, Argentina, Chile… there is too much bureaucracy and corruption and the funds do not go where they should. But then they keep asking, “Where will the next biodiversity summit be?”

What message could change this condescending way of operating on the part of the West?

I was hoping you could write this: We are destroying the planet, and then, we are allowing it to be destroyed.

How do you see future generations?

Last Friday, I told my son we just hit ten million trees planted, and he said, “You haven’t done anything yet.” I told him I had created 16 protected areas and given thousands of jobs to 25,000 families, but he insisted, “That’s nothing; we have to do much more.”

Young people want to enjoy what we have enjoyed until now, and they know that we must take action and be much more demanding of ourselves.

And the political context?

Yesterday, I met with other policymakers at an International conference in Brazil and with people from the United Nations, and they told me that poverty continues to increase. At the same time, they talk about $200 billion to finance nature conservation projects. What proportion of this money will be used to alleviate poverty?

The conservation of nature has to revert to the quality of life and the economy of local communities.

We have many corrupt governments, and those $200 billion will feed the bureaucracy; they are salaries for more consultants, budgets for more meetings…

Like you in This is My Earth, all I ask for is a dollar. Give me a dollar, and I’ll give you a tree and a smile. Give me one billion of the dollars you have, and I will plant one billion trees, reverse climate change, and alleviate poverty.

The great global hypocrisy of conservation is that it does not involve communities, neither local nor native. They are part of the solution; they understand the places where they live.

Is that what you do at Acción Andina?

From the beginning, we have involved local communities. Everyone wants us to come because we give them jobs, train them, and have a community approach, as they had at the time of the Inca empire.

The salaries we can pay are symbolic, but we pay them and invest in community benefits. But the government does not like this because we are going against a way of functioning that needs to be fixed.

With us, local and peasant communities benefit; and the governments of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Argentina are nervous. We are growing very fast.

How do you train people?

We help them work as they have always done, to manage the nurseries and use traditional ways. They have been monitoring the trees for ten months, protecting them from climate risks. This year, they have produced 3.5 million trees.

We do not victimize or have a paternalistic approach. Victimization is a thing that many organizations and governments like. They like to see a miserable person reaching out but don’t see them as part of the solution.

The problem is that victimizing yourself is an easy way to get funds but not an effective way to change things.

Is nature conservation a solution to poverty?

As long as you involve people, it is. In Peru, almost $100 million was given for a large-scale forest conservation program. That money only generated consultancies, a group studying things for five years and publishing a summary book — zero impact on local communities.

In 2019, in your speech to the United Nations, you said, “Enough.”

Yes, I said enough of comfort, enough of egos. They didn’t like it; these people sat there protecting their big salaries and egos.

We recently spoke with the NGO Para La Tierra in Paraguay, and they explained to us the degradation of the country’s forests due to the extensive exploitation of industry. How are native communities empowered to protect their resources?

This is almost the same question I was asked on CNN. If you don’t want to fail, you have, first, to have respect; second, listening skills; third, communication; and fourth, curiosity to learn from their wisdom. They have a lot to teach us.

I drive Quechua, Quichua, Aymara,… tomorrow I’m going to Córdoba [Argentina] to meet with the leaders of our organization — 55 people and we don’t fight.

The first time we were united in South America was during the Inca empire. The second time was when we fought for our independence. And this is the third time: to plant trees. There is no time for fights.

What is the challenge of planting trees in so many different bioregions?

We are using a set of tree species called polylepis. There are 46 species, which constitute the highest forest in the world.

We are improving how we do it, reducing the use of plastic. In Ecuador, we had problems due to a great hybridization of a specific species, but no one is born taught.

Is this going to solve climate change?

One day, people will understand all the damage they do to the planet, and native communities will be heard.

Will it be too late?

I have often been told, “Look; in the end, this will not end well.” I answer, “I will do my part to save time.” I should be in a ministry now, in a better-paid position, but this will not help future generations.

What do you think of the This is My Earth project?

Honesty and transparency are the best ways to change things, the best filter for things to work well. I thank you very much for what you are doing.

There should be more projects like TiME.