We had the privilege to talk to Dr. Clive G. Jones, founder of the field of ecosystem engineering by organisms and member of the board of directors of This is My Earth. He states that: “Preserving land with the biodiversity it contains is crucial. It not only protects habitat, but it also prevents the land use change that contributes to climate change”

It’s a pleasure to talk to you, Clive. Please introduce yourself.

I’m a member of the Board of This is My Earth. I have been on the board since the early days of TiME; 2016 as I recall. I am also an Emeritus Senior Scientist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, NY where I am a research ecologist.

Do you do science for This is My Earth?

Well, not really, although I do bring my scientific background in ecology and conservation biology to the table when it is relevant to thinking about and planning our mission. Where science is most relevant to TiME is in the rigorous criteria we use to select the biodiversity hot spots we want to protect and in evaluating how well our partners are doing in protecting them.

I don’t do that; the job is done by others at TiME — our distinguished Scientific Advisory Committee assisted by other Board members, volunteers and staff.

The things I do on the board are not scientific. They include governance, finance, fundraising and planning. I also provide input to our communication and education efforts. Naturally, my contributions are informed by science and by my connections to other scientists and conservationists, but that is not doing science.

How did you become interested in ecology?

I became interested in nature through my parents. I remember they would take me into the woods at night when I was a very young child.

We would walk and stop and listen to the sounds. It never seemed scary. Whenever we went on holiday, it was always a place with natural beauty. We rarely went to cities; it was mostly the countryside. My parents were both nature lovers. As a child, I would collect insects and watch birds. So throughout my childhood, I was constantly exposed to nature.

When I started school (and later at university), my inherent interest in biology and later ecology as a part of biology was awakened. Biology was the most exciting subject to me at school. It’s interesting for me to reflect on why that was. Was it the result of all that exposure to nature as a child, or was it just some innate curiosity in how nature works? Likely both!

You are best known scientifically as the founder of the field of ecosystem engineering by organisms. What is that?

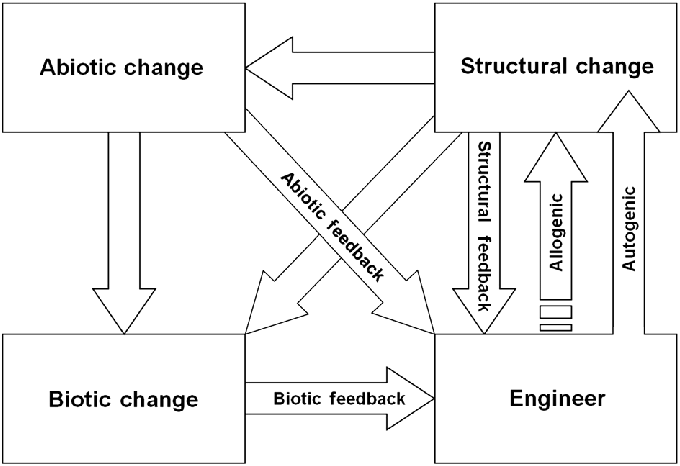

Ecosystem engineering is the scientific study of how species physically change the environment and the consequences for those species, other species and ecological processes. Ecosystem engineers create, modify and maintain habitats. The archetype animal engineer is the beaver.

Beaver build dams and create wetlands. They profoundly change hydrology, sediments, biogeochemistry, creating habitats for numerous species. In a general sense, however, beaver are not unique.

A vast number of species of animals, plants and microbes change the environments around them, creating habitats; from elephants making trails and waterholes, to coral reefs, to earthworms plowing the soil, to trees creating shaded cool, moist understory habitats, to microbial crusts that generate runoff water in deserts that are then used by plants.

How did you get interested in this topic?

I began my research career studying how plants chemically defended themselves against insects. At some point, while studying lichen chemical defenses in the Negev Desert, Israel, I got more interested in how all the organisms there, singly and collectively, appeared to be physically changing their surroundings to get water – the limiting resource in a desert. So for example, desert porcupines dig pits to eat bulbs and roots, and those pits trap runoff water.

Plants grow in those pits, and other organisms then depend on those plants, including porcupines! Ant mounds also trap water to similar effect. Geophytes grow underground, and then rapidly grow through the surface, making cracks in the soil. Runoff water then infiltrates into those cracks, and around the geophytes grow many plant species that use that water.

Microbial crusts make the equivalent of a plastic sheet secreted on the surface that funnels runoff water from rain into the pits, mounds and cracks. Without these engineering species the desert would be far less productive and biodiverse — most of the limited rain would just evaporate from the surface and be lost from the ecosystem.

So then I became interested in how general physical environmental modification by species was; in other words, beyond beaver or the Negev Desert. When looking at the ecological literature at the time, nature was largely viewed as being governed by predation and competition – nature red in tooth and claw!

Although scientists were aware of things like beaver dams and elephant trails, these kinds of influences were not seen as being central to understanding in ecology; it was all about predation and competition.

So the first ecosystem engineering paper we published in 1994 essentially said that nature is not just predation and competition. Physical environmental modification by species – the creation and modification of habitats – is pervasive and important, and we need to recognize that and study it.

Has the point of view of ecologists changed since then?

Yes indeed. Ecosystem engineering is now recognized as central to understanding in ecology, along with other processes like predation, competition, pollination and dispersal.

The study of ecosystem engineers and their effects is now a major research field within the ecological sciences.

It is widely taught at university and schools, and it has entered the public consciousness — you can find many articles about ecosystem engineers on the web.

Ecosystem engineering has also influenced other scientific disciplines including evolutionary biology, geomorphology, anthropology, and conservation biology/restoration.

Can you tell us about those influences on other scientific disciplines?

So in evolutionary biology it is now recognized that when new species of engineers evolve and then create habitats they also create opportunities for other new species to evolve in those habitats.

For example, when species that bio-turbated or reworked sediments first evolved they created habitats for new species that could live in those murky environments.

In geomorphology, scientists interested in how animals and plants affect soil formation and soil and rock erosion could now better connect those effects to the ecology of the species causing those changes. In anthropology, the historical role of human engineering in changing the environment to their benefit has become a major focus.

At the same time, the recognition that humans are ecosystem engineers “par excellence” has influenced the way scientists view human effects on the environment; has drawn heavily on the parallels with other species of ecosystem engineers; and has led to rethinking of strategies in conservation biology and habitat restoration.

Can you tell us a bit more about how ecosystem engineering has influenced conservation biology and habitat restoration?

Certainly. First, we can take the lessons learnt from studying how nature’s engineers create and maintain habitats and apply that understanding to the restoration and management of habitats — become the beaver if you like!

But second, perhaps we can also ask: if you want a new wetland or want to restore a degraded wetland, do you do it yourself, or do you get beaver to do it for you?

Beaver will do it for free; they’ll maintain it more or less indefinitely; and you’ll get all the benefits at little or no cost. If you just take care of beaver they will take care of the rest!

So putting nature’s engineers back to work is now becoming widespread in conservation and restoration – reintroducing beaver, recreating oyster reefs for the fisheries habitat they make and salt marshes for coastal protection, putting earthworms back into degraded agricultural soils, re-wilding with large animal engineers, and so on.

What can you tell us about where you work, the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies?

The Cary Institute is a private, non-profit ecological research organization founded in 1983 by Dr. Gene Likens, most known for his work on acid rain. It is a relatively small organization.

We currently have 14 staff scientists and a total staff of around 120 that includes postdoctoral associates, research support staff, educators, administrators, and emeritus scientists like me. We also have a vigorous visiting and adjunct scientist program, and we work collaboratively with many scientists throughout the world.

We do basic research relevant to real-world problems. We are not a university, but we are an academic organization.

We are non-profit, raising funds for the science and education programs, mostly from federal and state grants.

We may be small but we are recognized as one of the premier ecological research institutes in the world, with work that has not only had major influences on scientific understanding, but also environmental policy and management.

I note from our recent newsletters that you are involved in the “TiME for Birding for Conservation” initiative. Can you tell us about that?

TiME for Birding for Conservation is a conservation-orientated fund-raising birding trip to Ecuador we are organizing for February 2024 with our partners – Flyways Birding and Nature run by Jonathan Meyrav in Israel, and Jocotours, part of the Jocotoco Foundation in Ecuador. We have three goals.

The first is raising funds to help the Jocotoco Foundation purchase a biodiversity hotspot adjacent to their reserve in Tapichalaca – one of the sites that the Scientific Advisory Committee has put forward as a target.

The second is promoting TiME and its important mission. The third and final goal is to raise awareness of the potential for birders to contribute to the conservation of the very places they want to visit to see birds – birding for conservation.

We hope to do some promotional and educational webcasts from Ecuador, including events for children.

We are asking participants to make a donation to TiME that will be used to help purchase land in Tapichalaca.

The trip is not yet fully booked up, so if you are interested in knowing more, in going on the trip, or know someone who might be interested, you can find out more on the TiME website trip page and at Flyways Birding and Nature.

How did the idea for the trip come about?

It all began when a friend who is a renowned ecologist and avid birder made a donation to TiME to help us acquire the hotspot in the Chocó forest, Ecuador. Thanks to him and many other TiME donors, we raised the funds for the Jocotoco Foundation to acquire more land for the reserve in the Chocó Forest in 2022.

He and I had some conversations about TiME and birds when I thanked him for the donation. I asked him if he had visited the Chocó.

He said he had been birding in Ecuador – it is one of the most bird-biodiverse places on the planet — but had not been to the Chocó and would love to see the Banded Ground Cuckoo – a rare, reclusive species found only in the region. So that left me thinking that perhaps we could organize a fund-raising trip for birders that would visit the land we had helped protect in Chocó and the land at Tapichalaca we are currently trying to protect, while helping promote TiME and its mission.

TiME has never done anything like this before, but when I suggested it to Uri Shanas, TiME’s CEO, he said something to the effect of… “I would do anything to go on a trip like that.” Then Uri told me that Jonathan Meyrav, who’s been featured in one of our previous newsletters and runs tours for Birdlife Israel, also has a birding tour company called Flyways Birding and Nature.

Flyways is orientated around fundraising for conservation and has donated to TiME. Jonathan was very interested in the idea and was willing to lead a trip that would help promote the idea of birding for conservation.

It also turned out that the Jocotoco Foundation, who manages reserves in the Chocó and Tapichalaca and is one of our partners, has an ethical ecotourism division, Jocotours, who was willing to help plan the trip itinerary and have their local birding expert, Juan Carlos Figueroa, help lead the trip.

So all the many ingredients somehow came together and we launched the trip with an announcement in May.

As I said, there is still an opportunity for people to join us in what will be an exciting and important trip that will help protect critical habitat for birds and other species in perpetuity.

Why do you think This is My Earth is necessary?

Of the many environmental crises we face, two are huge challenges. One is, of course, fossil-fuel-induced climate change. The second is land use change. They’re connected.

Land use change – primarily deforestation – massively contributes to climate change. Indeed, deforestation is the second leading cause of carbon emissions. So land use change is a very big problem from a climate change perspective. But it is also, of course, a massive problem with respect to biodiversity.

Biodiversity requires space and that space must be suitable. So if you’re going to convert all of the land to other uses, then irrespective of the climate consequences, you will eliminate habitat for species. Preserving land with the biodiversity it contains is crucial. It not only protects habitat but it also prevents the land use change that contributes to climate change. Furthermore, it is far easier to protect land with the biodiversity it already contains than it is to convert former agricultural land back into forest and hope the species that were lost will then return.

So one of the most important things we can do is to protect land with biodiversity. That is what TiME focuses on — saving those biodiversity hotspots and ensuring they persist, while connecting as many of them as possible so you have large amounts of space for those species.

We are a small organization. We don’t have the funds to buy vast tracts of land. So we focus on raising the money to get critical corridors and extensions to existing habitat. While protecting biodiversity hotspots is not unique to TiME, it’s undoubtedly an essential and central aspect of TiME.

The second aspect that is important to me is the democratic nature of This is My Earth. In other words, This is My Earth means it belongs to all of us. Donating to become a member allows you to be a part of the ownership and stewardship of your Earth.

Private land is the best way TiME can move forward — we are not in the business of convincing governments to preserve more land; other people and organizations try to do that.

What we want to do is to take private lands rich in species that are potentially threatened and would otherwise be converted, and preserve them forever. And if we act collectively to do this then, in a sense, It Is As Much Your Earth As It Is My Earth.

And TiME is not just democratic because we all vote on which lands most deserve to be saved, it is also democratic because everyone gets only one vote.

If you give a dollar or you give $10,000, you have the same say in which land we collectively decide on. So the democratic nature of TiME is a great way to engage people in active governance and stewardship of the planet.

Is there any other aspect of TiME’s mission you think is important?

Yes, education! The next generation and the generations after that, will inherit the Earth that we leave them today — for good or bad. And so the young people of today need to learn about biodiversity, and they need to learn how they can actively take steps to protect it.

Our education programs do exactly that. Young people learn about biodiversity and the sites we are putting forward to protect.

They raise money, become members, and vote for the land just like anyone else. They make it their Earth just like any other member, while carrying our mission forward in time.

There are a lot of conservation organizations out there helping protect biodiverse lands. But to me, what makes TiME unique is the combination of land conservation, democracy, and education.

Thank you very much for your TiME!

My pleasure!