We had the privilege of interviewing Nira Fialho, executive director of our sister organization Instituto Uiraçu.

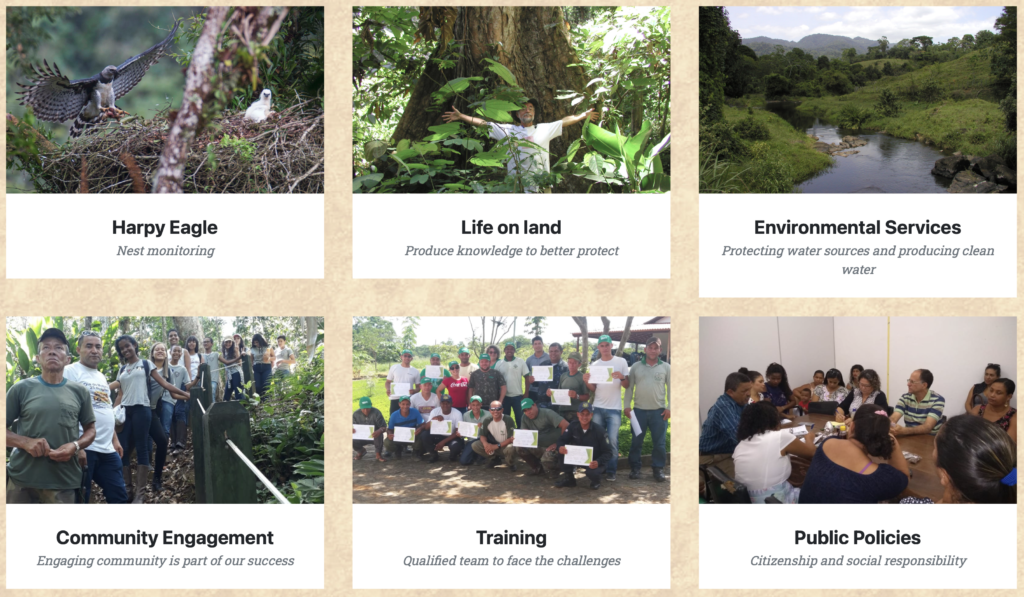

Instituto Uiraçu is a private, non-profit, technical-scientific entity in the mission of “Preserving, protecting, conserving and recovering Atlantic Forest ecosystems” through the maintenance of Conservation Units, monitoring these areas, production of scientific studies and projects with social and environmental impact.

With Instituto Uiraçu, we share a beautiful success story in Serra Bonita. In 2020, TiME’s land purchase allowed for the expansion of the Serra Bonita Reserve (SBR) in Brazil’s most endangered biome and the world’s second-most threatened hotspot. In addition to protecting many threatened species, this expansion ensured the survival of predators that require large, unbroken territories, like the Puma (Puma concolor) and the Harpy Eagle (Harpia harpyja). Visit the land saved on Google Maps here.

Here you can see the place where this NGO is located:

How would you introduce yourself?

Oh, I never thought about that. I want to introduce myself as an environmental professional.

Can you recall a moment of revelation regarding the importance of nature conservation?

As a teenager, I remember debates between my parents and uncles about the possibility of deforesting a dense forest that was part of our family’s land.

The reason behind this discussion was the need to make their path safer when returning home after long working hours, as crossing that dark and gloomy area at night often became a haunting experience.

The journey through that forest, however, was of singular beauty. The movements of the animals in the bushes and dense vegetation were enough to make our legs shake with genuine fear.

However, something inside me refused to accept the proposal for deforestation of that vibrant and dazzling forest due to the fear that people had of the dark and the movements of animals in the bushes.

In addition to the aesthetic aspect, there was a practical and crucial reason for our family to become attached to that forest: the existence of a spring whose waters gushed vigorously and freshly, supporting a small ecosystem that played a significant role in our lives.

This was an episode in my life that made me realize that I wanted to work to defend nature and all its abundance, which we enjoy so much and which we need to live happily.

What can you tell us about how your organization, Instituto Uiraçu, works?

At Instituto Uiraçu, we work for the preservation of threatened and endemic species.

We are a private, nonprofit entity of a technical-scientific nature.

We seek to fulfill the mission of “Preserving, protecting, conserving and recovering ecosystems of the Atlantic Forest” through maintaining conservation units, monitoring these areas, and producing scientific studies and projects with social and environmental impact.

One of our most important missions is to expand habitats for species that need lots of space. Our strong focus is on purchasing land to develop these habitats. We want them to be perpetually preserved.

We seek to fulfill the mission of “Preserving, protecting, conserving and recovering ecosystems of the Atlantic Forest”

What are the main activities you carry out at your organization?

Our institution deals specifically with three types of actions. First of all, bird watching.

We allow birders and visitors to come and do bird watching. We also have an environmental educational area focused on ecological production and showcase a demonstration unit for preservation.

The last time we talked, you introduced us to the exceptional cocoa culture of your Brazilian region. How is the situation today?

It is a significantly threatened area. We have 11 lower productivity areas today due to a plague. One of the weeds here has a powerful tendency to expand.

Also, there’s the issue of coffee planting, which is increasing the levels of deforestation.

Dismantling the forests means causing different impacts on watercourses, springs, and rivers, and… the local population.

In general terms, this is a very precious and vital region that needs to be bought and protected forever.

What are the natural resources at risk for the local population?

Water is the main problem. Without the protection of a healthy mountain, the local communities here would no longer have water available.

We must acquire more properties and land to expand the areas and protect the entire ecosystem.

We also need to keep strengthening our commitment and responsibilities with the local producers and make sure they work with us in the same direction so they are also protecting the area.

What are the sizes of the available proprieties to buy?

Most of them are between 50 and 100 hectares. They are relatively small. We only need a little money to protect them. It’s more about bureaucracy.

How did your relationship with This is My Earth start?

I received a referral and a contact from This is My Earth. I saw TiME’s website and your group of researchers, biologists, and environmental scientists. Your project was transparent and calm, so we decided to submit this particular project.

Our experience with This is My Earth has been profoundly positive. We would only change the working tempos, as TiME is volunteer-based, and volunteers have other jobs, interests, and priorities.

We must acquire more properties and land to expand the areas and protect the entire ecosystem.

Of all the species in your area, which is your favorite?

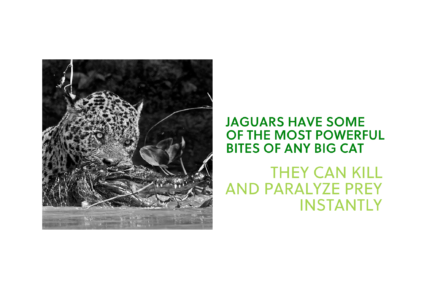

Good question. My favorite one is a bird, a bird called a Harpy Eagle.

They are one of the most important quality indicators for conservation. If they appear, that means forests are healthy.

They only require a little space to eat, so if they are there, it’s because there is enough food and diversity in the area for them to live. If you see them, you know things are working well.

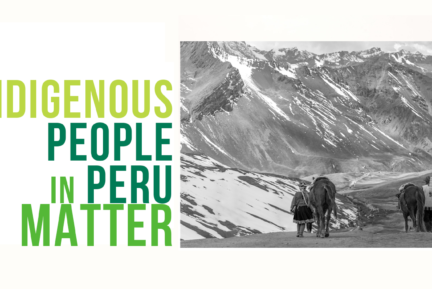

What can you tell us about the political situation in Brazil regarding the Supreme Court ruling in favor of indigenous rights over their lands?

The main problem has been that the president has tried to veto some of the contractual clauses regarding land ownership. And we have a Congress in which most MPs are against environmental policies.

Former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s group had a lot of power, and they were against the expansion of indigenous areas because they wanted to make money from these areas.

That is, they want to destroy the indigenous forest.

What are the most prominent industries interested in promoting this destruction?

There are mining companies and large soybean landowners. What they are trying to do goes against the 1988 Constitution, so we still may have a chance to stop it.

A couple of weeks ago, we talked to the Paraguayan NGO Para la Tierra, and they explained to us how significant the problem of the soybean fields is. How are you dealing with this issue in your region?

The large properties of soybean fields are in indigenous lands in the Amazon. This is the most crucial focus of soy and mining. The problem is not just big companies; the issue of mining also involves small private projects. Mining is a profoundly irregular economic activity in the Amazon.

Lula – Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva – wants to stop the economic exploitation of these areas and the entry of military personnel and promote the creation of new requirements for daily demarcation.

However, Congress is more aligned with Bolsonaro’s ideology and has expressed its will to block Lula’s initiatives. So, it can be challenging.

Brazil has vast indigenous areas, which are very important for environmental protection.

They are more significant than any federal conservation area. So, everyone is watching these territories for their strategic position and resources.

Some weeks ago, we had the chance to interview Eddie Game, director of The Nature Conservancy in the Asia-Pacific region. He told us about ecoacoustics, the science that studies how the health of an ecosystem can be determined by its sounds, and he told us that the Earth is becoming silent. Have you noticed that in Brazil?

In our area, we are lucky because there are many species of birds, but it is true that there are fewer than before.

This “going silent process” is indeed seen in a large part of the Amazon; there are more occasional sounds than when I was a kid.

Thanks for the input; we will include the topic of ecoacoustics in our education activities!

What final message would you like to share with the This is My Earth community?

We are in a very critical moment. Environmental issues around the world need to be addressed. Extinction, the increase in temperatures, pollution… We need to invest more efforts in education.

We need more support to buy all the lands in Brazil’s beautiful Serra Bonita area. And we need more people to do the same worldwide. We also need resources and technology to improve the quality of nature conservation work.

So, every kind of help is needed, and any contribution is welcomed.