The only nature conservation nonprofit Jordi Vilanova knows in which 100% of your donation goes to where it’s needed is This is My Earth. “We need to integrate all sorts of knowledge,” the PhD student and TiME volunteer say.

What brought you to study Ecology and Biology?

Ecosystems and animals have always interested me. When I started my Master’s, I liked primates, such as monkeys and chimpanzees… and then I found out that there are so many more fascinating animals; among them, I’ve fallen for the ants’ field.

Why ants?

Ants are crucial for ecosystems; you need to study ants to understand how they work and maintain their balance.

Why are you so passionate about them?

How many they are compared to us makes you wonder what our place is on this planet. Some studies say that 15% to 25% of total animal terrestrial biomass is made of ants. So if you put together all sorts of animals, you can imagine about 20% would be ants. It is a tiny creature, yet they are so highly abundant! It is very appealing.

Dave Goulson was one of your teachers, and in a recent interview with TiME, he made us think about this idea of an alien looking at our planet and defining it as the “planet of the insects.” How threatened are insects in our world?

Everyone knows about the use of pesticides and how our agricultural practices right now are not sustainable. We are taking some measures. We are moving in the right direction so that the impact of these practices is less severe. There is still a long way to go. One of the significant issues here is land use changes. When you take an unspoiled piece of land and turn it into a supermarket, you will be destroying — for good — a lot of biodiversity there.

We can see these changes every day. We, as young people, don’t know, but not so long ago, when you drove your car across the country, you would need to stop occasionally to wipe insects from your windshield. Now you don’t have to do it. That means there has been a massive decline in insects worldwide. Protecting habitats is crucial. For that, you need to collaborate with projects such as TiME, where your donation goes to where it’s needed.

Are ants more threatened than other insects?

Ants are remarkably resilient. For instance, an excellent study by Sarah E- Diamond & Co shows that ants’ population numbers don’t change but their fragility increases, so they become less resilient. Climate change is weakening ants.

Are there any particular changes in their community behaviors due to climate change?

We can see changes in their communities; the colony sizes are changing, mainly decreasing, which is very likely to affect how individuals behave.

Between Frederic E. Clements and Joseph H. Connell, which one of the two leading schools on biodiversity studies in the 20th century would you be a supporter of, that of studying individuals or understanding communities as a whole?

At this point, we should holistically analyze things; we need to integrate all sorts of knowledge and the evidence we can gather. Many different things threaten insects, so you need to gather all these aspects together to come up with a valuable understanding of what’s going on and to find an excellent solution. There is this concept of consilience, the unity of knowledge. I believe in what people like Edward Wilson defended; Everything is connected.

What about humans? How is climate change affecting our behavior as a community?

I think the interesting question is, will we cooperate more as humans with fewer resources? And I think the answer is complex. On the one hand, we are collaborating more, with globalization, with many exchanges between countries and in deeply diverse societies. Of course, resources are decreasing, but maybe our most significant threat is not the lack of them but their unwise use. It seems to me, we don’t make clever use of our position on this planet. For example, there are plenty of fish in the world, but we have decided to explore some areas with damaging fishing techniques. Continuing like this creates a deep unbalance in marine ecosystems.

Born in Barcelona, you’ve also lived in Canada and Africa, you’ve visited Taiwan, and recently, you finished your Master’s in Hong Kong. Having seen so many different civilizations and cultures, do you think it’s possible to stop climate change?

I am hopeful. I’m hopeful because there is no alternative; we need to solve this issue and do it fast. We need to change. And we should change our way of working, living, and thinking. If we want to thrive, there’s no other way. What’s the point in unique projects such as This is My Earth if you are not hopeful? Stay hopeful and work hard; we can do it. And you can be sure about the fact that your donation goes to where it’s needed.

Some would argue that as a Western white man, it’s easier to say these things because you’ve had lots of chances to get a good education, to travel, and to think “outside of the box” — and by doing so, you have polluted much more than other citizens of the planet. How would you respond to that?

I have indeed taken the plane much more than I should have. However, I have recently tried to reduce my plane travel as much as possible, trying to avoid it if there’s a more sustainable transportation method. However, I must accept that taking a plane was more convenient for pursuing some of my research. It is not the best, and I acknowledge that.

What country do you think has an excellent alternative transportation network?

Germany has a functional, sustainable, fast train network; you can virtually go everywhere.

Technologies like the internet might help us become more sustainable; for instance, you have now finished your Master’s in Functional Ecology and have done so fully online. What can you tell us about it?

This Master’s aims to help us understand how things work inside ecosystems because we all hear that biodiversity is essential and that we must take care of ecosystems. Still, when you hear that on TV, you don’t know why this is important. In this Master’s, we learned why the tiger is essential, the jellyfish’s role, etc.

And why are ecosystems so important?

I support the school of thinking that emphasizes the intrinsic importance of ecosystems, meaning ecosystems are essential just because they are. On a more scientific basis, of course, a lot of data and evidence support the idea of the importance of an ecosystem; all animals rely on ecosystems, and we also use them. Ecosystems are at the heart of many things we do, from tourism to healthcare.

What about this trend supporting the idea of using ecosystems and biodiversity to fight climate change and slow global warming?

We can indeed make use of ecosystems to find solutions to climate change. However, using this expression of “making use of nature,” perhaps we can find a better alternative; it sounds so capitalist… We need to fight climate change by all the means possible, and we need to do it properly. We know that restoring ecosystems makes a difference in this fight. Preserving biodiversity will allow these ecosystems to thrive. We know that donating to transparent nonprofits such as TiME is the correct thing to do because your donation goes to where it’s needed. We will lie to ourselves if we think that we can fight against climate change through a business or economic approach.

Can you recall a moment during your last years of training in which you realized you were learning a lot?

One of the times I truly felt I was learning a lot was when I conducted a small study in Senegal on chimpanzees with the Jane Goodall Institute Spain. I remember going there while they were planting their crops, and everyone was freaking out. They told me that rains were coming two weeks later than they should and that this would have a massive impact on their ecosystem.

You cannot be sure that these late rains are because of climate change; however, meteorologists from EUMETSAT often say, “Nothing in climate is happening anymore without taking into account climate change.” This event touched me deeply. Because their lives depended on those rains, and this delay was critical for their survival. If you think about it, it is very unfair, these people are among those who have contributed the least to climate change, yet they are the most affected by it.

What about your colleagues? What have you learned from them?

I’ve learned to be optimistic. We have to tackle climate change; there’s a lot of work to do. Still, seeing so many people in the ecology and conservation fields working very hard and being optimistic about their work, especially new generations, is encouraging. I know many young people are very eager to bring about change and make a difference. I see a significant segment of society just accepting what is happening, probably because they feel helpless. But working with these young people gives strength, so you think there are ways to care and induce change in the broader community. They want to engage in projects. They want to ensure that the donation goes where it’s needed.

Do you recall any situation in which you felt outraged?

I remember an obvious situation. Many years ago, my cousin told me something like, “Yes, climate change is bad, but for 30 years or more, we have been sending the same message: ‘We have to hurry up, there’s no time left, things are getting worse and worse… etc.,’ but it looks like nothing has significantly changed.” That made me very angry because I thought we wanted things to change, but we could not change the message; what was wrong with us? We’ve been saying, hey, the wolf is coming for decades. Although it is getting closer and closer, we don’t seem to find the means to engage a broader audience to join our ecological fight. It is undeniable that efforts in communication are taking place globally.

Warnings about climate change and global warming are overwhelming.

With climate change in particular, at least in our corner of the world, we see the effects of climate change, but we don’t associate them with human activity. For example, it hasn’t rained in Texas in a long time, and the media has started discussing desertification. But perhaps this concept is too complex to be understood by the general public; maybe we have to find more personal messages to make it each person’s business.

How can TiME help?

When you collaborate with TiME, you can be sure that your donation goes where it’s needed. I think that This is My Earth puts words into practice because there are always areas that need protection, and TiME offers people the chance to protect these areas and the right to vote and choose which one to save. This is My Earth empowers people; you feel you are actively doing something to fight climate change. If we can show that our actions improve the situation, this will engage more people.

Did you tell your friends that in This is My Earth your donation goes to where it’s needed?

At first, they were very skeptical because most of my colleagues work in the field of conservation, ecology, and biology. When we hear about a project such as TiME, the first thing that comes to mind is “greenwashing.” But once you explain it well, everybody in my field and age group feels very motivated.

Is it something like “this is too good to be true”?

Somehow yes, it feels like it, but in truth, it’s true!

What does your future look like?

I have to go through four years of my PhD in Canada. My PhD is about biogeography and community ecology. My approach is that little changes in temperature, rain, and weather directly affect ants’ behavior. And after this, I want to keep learning. I want to help an organization such as TiME where your donation goes to where it’s needed. I would love to be able to work or collaborate with one of these international organizations and help them make sensible decisions about climate and our planet.

What will you do for TiME?

I will bring awareness about This is My Earth and explain our project. Also, we will try to create TiME groups at universities so more and more people engage with This is My Earth. I want to help TiME grow because This is My Earth is the only nature conservation nonprofit I know in which 100% of your donation goes to where it’s needed. With TiME, your donation goes to where it’s needed, and that is crucial.

What is your favorite piece of art against climate change?

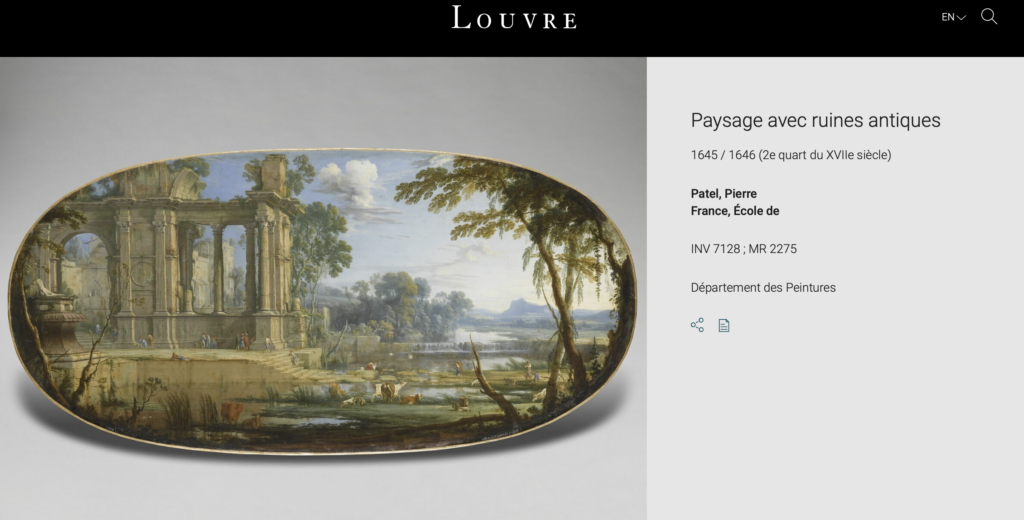

I think it is this painting from Pierre Patel called “Imaginary Landscape with Classical Ruins“; it has a very particular atmosphere connecting human architecture and nature as if they were conversing.

Thank you so much for your TiME, Jordi, and best of luck!