We had the privilege to talk to the NGO Para la Tierra about nature in Paraguay. Its Director Rebecca Smith, originally from Scotland, and Communications Officer Olivia Zickgraf share with TiME why Paraguay and its biodiversity are important.

How would you introduce yourself?

Rebecca: I am Dr. Rebecca Smith, director of the Para La Tierra Foundation. I am a primatologist. I study monkeys; that’s why I came to study nature in Paraguay.

I am originally from Scotland and have lived in Paraguay for 11 years. My personal and professional objective is conserving and protecting monkeys and forests.

Olivia: My name is Olivia Zickgraf, and I am from Germany. I studied psychology with a focus on marketing and communities. After my Master’s, I came to Paraguay to work with Fundación Para La Tierra. I have managed marketing and communication for Para La Tierra for a year and a half.

On a personal level, what moment do you remember from your youth in which you realized that nature was in danger?

Rebecca: It was when I was already in Paraguay. I came here to study monkeys; I wanted to know about their behavior.

During the first four years, we were in a private reserve in the northeast of Paraguay called Laguna Blanca; in the department of San Pedro, there were almost no forests left.

It is tough to ignore the situation of nature in Paraguay when traveling for hours and hours through soybean fields in places where there should be forests.

Who is all this soy for?

Rebecca: It is soy produced for industry. In the year 2015, I went to take several volunteers from Laguna Blanca to the Mbaracayú reserve.

It was a trip of about 7 hours, and we played the game of I Spy but, for hours, everything was homogeneous. The only thing we would see was soybeans.

In the Atlantic Forest area of Paraguay, we have already lost about 92% of our forests, mainly due to industrial soybean production.

And for you, Olivia?

Olivia: When I was in Germany, I recycled. I knew about the importance of conservation and the dangers of climate change, but always in a theoretical way.

I came here thinking, “We are going to change the world,” but when I saw the soybean fields and the destruction of the Atlantic Forest, I realized that we have to do bigger things to protect nature.

And as an organization, what is your mission?

Rebecca: Our organization’s mission is to conserve nature in Paraguay. We protect the country’s biodiversity.

We use scientific research, community work, and environmental education to achieve this goal.

What is it that makes Paraguay such a unique country?

Rebecca: Because it is in the heart of South America, it has an unusual mix of habitats. Nature in Paraguay is highly diversified.

Not many people think of Paraguay as a place to study biodiversity or the natural context. It is a country to discover — full of secrets.

It is also a site that has undergone a radical change. In 2000, Paraguay had the highest deforestation rate in the world.

On your website, you explain that only 2% of the original forests remain in the country…

Rebecca: Yes. The problem with soybeans is in the Atlantic Forest. In the north of the country, The Gran Chaco, the problem is livestock, not just for meat production, but also the leather industry; it is used for cars, Mercedes, BMWs…

There are also fires and more minor crops… but they are much less of a risk to the forests. Sometimes, people blame the locals for it, but people who hunt for their family to eat or cut down some trees for their private use would not pose a relevant risk if the majority of the forest had not already been destroyed by industrial agriculture.

The soybean and cattle industries are the main problems.

In 2000, Paraguay had the highest deforestation rate in the world.

How does your program work — you invite volunteers to work with you?

Rebecca: We have an internship program and one for volunteers. Those who want can come here to do their research.

Olivia: Both volunteers and scientists can participate in the projects and learn about scientific research methodologies. They all help us with our environmental education program and at the museum, where they know how to exhibit and disseminate science.

What feedback do they give you?

Olivia: They’re happy. Most come here after finishing their university studies. They are thinking, “What do I want to do next with my life?”

The vast majority want to work with animals and are looking for a field of research.

Usually, this experience with us in Paraguay gives them an idea of what they want to do.

Rebecca: We help them publish their paper, and many leave here with a good personal experience and a scientific publication.

To learn a bit about the reality of conservation, they often come with me to work in the Atlantic Forest and have the chance to participate in our programmes with

our Indigenous Mbya Guaraní partner communities in eastern Paraguay, the

Guaraní.

These communities are relatively closed… we are the only ones working with them. It is a profound experience for our volunteers, something that, in Europe or the United States, they cannot learn.

In what sense?

Rebecca: Not all Aboriginal people have a nature-protection mentality.

In reality, only one Indigenous group or community in the Amazon wants to protect the forest. It doesn’t mean they don’t appreciate the forest, but they have other priorities.

Learning about the real world of nature conservation is learning that not everything is always easy or black and white.

Is it a culture shock?

Rebecca: I think it’s more of a clash between expectations and the idea of reality.

In our NGO, many volunteers leave the university and arrive with a preconceived notion of what an Indigenous person is or what a nature conservator does. When looking at nature in Paraguay, most of them come with a Western mindset.

Learning nature conservation is learning that not everything is black and white

Did it happen to you, too?

Rebecca: When I arrived, I came with the mentality of, “I’m going to go to Paraguay and explain to people that the monkeys are cute, and nobody is going to want to cut down the forest.” Obviously, that’s not how it works. Working with Indigenous peoples is an opportunity to open your mind.

How do you keep your scientific paper collection up–to–date?

Rebecca: We encourage and offer our visitors the possibility of publishing in scientific journals. There are very few studies on Paraguay, so there are many new things to learn. Scientists have to collect data for at least three months.

In addition to publishing in journals, they also present their studies at international conferences, which helps a lot to make Paraguay known and show that it is a worthwhile place for conservation.

How does the museum you have work?

Rebecca: Our museum is a natural-history collection. It is the second largest in the country. Only the national collection of Asunción is larger than ours.

Most of the large mammals in our museum collection are found run over on the roads. It’s sad when we see an animal run over, and we take its body to our house. We also have insects, frogs, small lizards…

Our museum is a significant inheritance of Paraguay.

At the level of communication, what response do you receive from the audience in Paraguay?

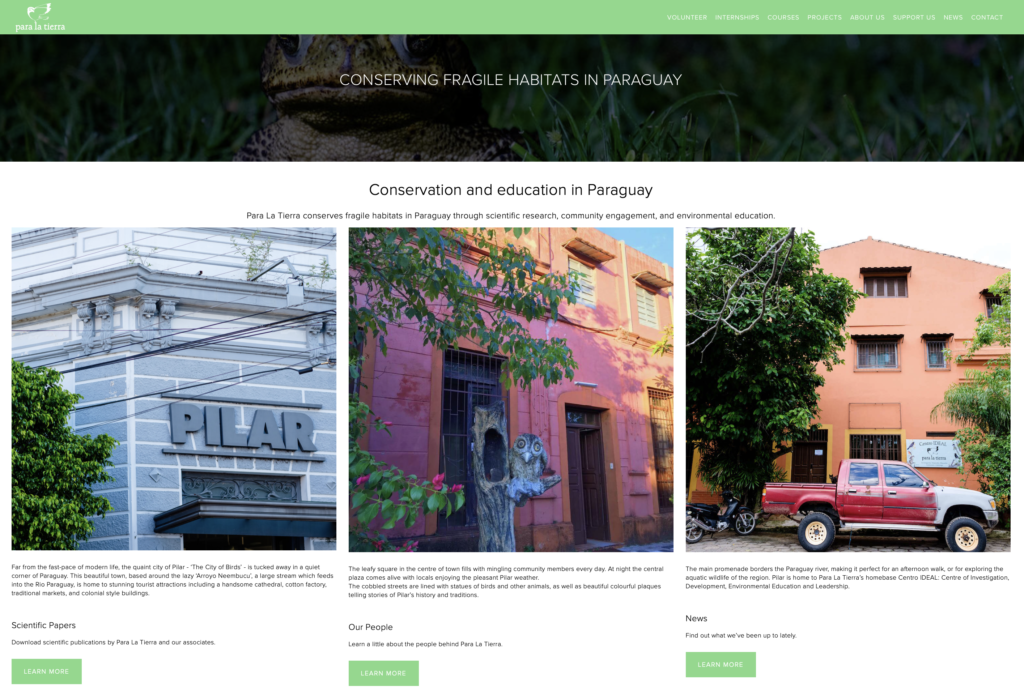

Olivia: I think the response is very positive, especially in Pilar and Asunción, as well as in the rest of the big cities in Paraguay.

People are very open to conservation and understand that we have climate change and must change.

In our social networks, we explain many natural secrets of Pilar where Para La Tierra is based and Paraguay.

We also have several educational projects, precisely our Voces de la Naturaleza eco-clubs, where boys and girls are trained on the importance of biodiversity. Among other things, we have built a dump, collected trash, and helped people recycle.

How can I adopt a monkey?

Rebecca: Easy! Enter our website and investigate the profile of the monkeys. Each one has its personality. Some are very curious, others a bit lazy… we have a story for each of them, and you can think which one you like the most. Fill in the form and adopt it.

We will contact you and send you photos of how life is going, his day-to-day, his new friends, his health, and his particular characteristics.

Olivia: We also have baby monkeys. You can name them, too!

How do you see the connection with This is My Earth?

Rebecca: I see us collaborating in the future, yes. Nobody thinks about Paraguay, but looking at the TiME website and annual report, there is room for our project.

Our long-term goal is to buy land and set up a private nature reserve. TiME can help us.

What final message do you want to send to the community of followers of This is My Earth?

Rebecca: I want to thank everyone fighting for conservation and invite you to meet and come to Paraguay.

Olivia and Rebecca: Many thanks for your work.